by James C. Anderson, James A. Narus, and Wouter Van Rossum

“Customer value proposition” has become one of the most widely used terms in business markets in recent years. Yet our management-practice research reveals that there is no agreement as to what constitutes a customer value proposition—or what makes one persuasive. Moreover, we find that most value propositions make claims of savings and benefits to the customer without backing them up. An offering may actually provide superior value—but if the supplier doesn’t demonstrate and document that claim, a customer manager will likely dismiss it as marketing puffery. Customer managers, increasingly held accountable for reducing costs, don’t have the luxury of simply believing suppliers’ assertions.

Take the case of a company that makes integrated circuits (ICs). It hoped to supply 5 million units to an electronic device manufacturer for its next-generation product. In the course of negotiations, the supplier’s salesperson learned that he was competing against a company whose price was 10 cents lower per unit. The customer asked each salesperson why his company’s offering was superior. This salesperson based his value proposition on the service that he, personally, would provide.

Unbeknownst to the salesperson, the customer had built a customer value model, which found that the company’s offering, though 10 cents higher in price per IC, was actually worth 15.9 cents more. The electronics engineer who was leading the development project had recommended that the purchasing manager buy those ICs, even at the higher price. The service was, indeed, worth something in the model—but just 0.2 cents! Unfortunately, the salesperson had overlooked the two elements of his company’s IC offering that were most valuable to the customer, evidently unaware how much they were worth to that customer and, objectively, how superior they made his company’s offering to that of the competitor. Not surprisingly, when push came to shove, perhaps suspecting that his service was not worth the difference in price, the salesperson offered a 10-cent price concession to win the business—consequently leaving at least a half million dollars on the table.

Some managers view the customer value proposition as a form of spin their marketing departments develop for advertising and promotional copy. This shortsighted view neglects the very real contribution of value propositions to superior business performance. Properly constructed, they force companies to rigorously focus on what their offerings are really worth to their customers. Once companies become disciplined about understanding customers, they can make smarter choices about where to allocate scarce company resources in developing new offerins.

We conducted management-practice research over the past two years in Europe and the United States to understand what constitutes a customer value proposition and what makes one persuasive to customers. One striking discovery is that it is exceptionally difficult to find examples of value propositions that resonate with customers. Here, drawing on the best practices of a handful of suppliers in business markets, we present a systematic approach for developing value propositions that are meaningful to target customers and that focus suppliers’ efforts on creating superior value.

Three Kinds of Value Propositions

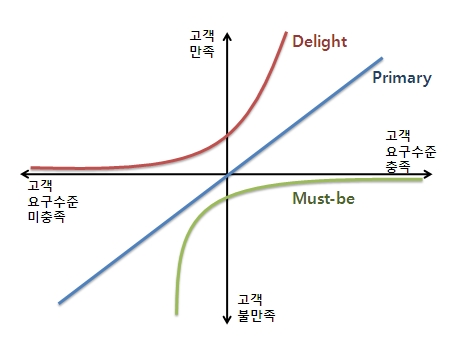

We have classified the ways that suppliers use the term “value proposition” into three types: all benefits, favorable points of difference, and resonating focus. (See the exhibit “Which Alternative Conveys Value to Customers?”)

All benefits.

Our research indicates that most managers, when asked to construct a customer value proposition, simply list all the benefits they believe that their offering might deliver to target customers. The more they can think of, the better. This approach requires the least knowledge about customers and competitors and, thus, the least amount of work to construct. However, its relative simplicity has a major potential drawback: benefit assertion. Managers may claim advantages for features that actually provide no benefit to target customers.

Such was the case with a company that sold high-performance gas chromatographs to R&D laboratories in large companies, universities, and government agencies in the Benelux countries. One feature of a particular chromatograph allowed R&D lab customers to maintain a high degree of sample integrity. Seeking growth, the company began to market the most basic model of this chromatograph to a new segment: commercial laboratories. In initial meetings with prospective customers, the firm’s salespeople touted the benefits of maintaining sample integrity. Their prospects scoffed at this benefit assertion, stating that they routinely tested soil and water samples, for which maintaining sample integrity was not a concern. The supplier was taken aback and forced to rethink its value proposition.

Another pitfall of the all benefits value proposition is that many, even most, of the benefits may be points of parity with those of the next best alternative, diluting the effect of the few genuine points of difference. Managers need to clearly identify in their customer value propositions which elements are points of parity and which are points of difference. (See the exhibit “The Building Blocks of a Successful Customer Value Proposition.”) For example, an international engineering consultancy was bidding for a light-rail project. The last chart of the company’s presentation listed ten reasons why the municipality should award the project to the firm. But the chart had little persuasive power because the other two finalists could make most of the same claims.

Put yourself, for a moment, in the place of the prospective client. Suppose each firm, at the end of its presentation, gives ten reasons why you ought to award it the project, and the lists from all the firms are almost the same. If each firm is saying essentially the same thing, how do you make a choice? You ask each of the firms to give a final, best price, and then you award the project to the firm that gives the largest price concession. Any distinctions that do exist have been overshadowed by the firms’ greater sameness.

Favorable points of difference.

The second type of value proposition explicitly recognizes that the customer has an alternative. The recent experience of a leading industrial gas supplier illustrates this perspective. A customer sent the company a request for proposal stating that the two or three suppliers that could demonstrate the most persuasive value propositions would be invited to visit the customer to discuss and refine their proposals. After this meeting, the customer would select a sole supplier for this business. As this example shows, “Why should our firm purchase your offering instead of your competitor’s?” is a more pertinent question than “Why should our firm purchase your offering?” The first question focuses suppliers on differentiating their offerings from the next best alternative, a process that requires detailed knowledge of that alternative, whether it be buying a competitor’s offering or solving the customer’s problem in a different way.

Knowing that an element of an offering is a point of difference relative to the next best alternative does not, however, convey the value of this difference to target customers. Furthermore, a product or service may have several points of difference, complicating the supplier’s understanding of which ones deliver the greatest value. Without a detailed understanding of the customer’s requirements and preferences, and what it is worth to fulfill them, suppliers may stress points of difference that deliver relatively little value to the target customer. Each of these can lead to the pitfall of value presumption: assuming that favorable points of difference must be valuable for the customer. Our opening anecdote about the IC supplier that unnecessarily discounted its price exemplifies this pitfall.

Resonating focus.

Although the favorable points of difference value proposition is preferable to an all benefits proposition for companies crafting a consumer value proposition, the resonating focus value proposition should be the gold standard. This approach acknowledges that the managers who make purchase decisions have major, ever-increasing levels of responsibility and often are pressed for time. They want to do business with suppliers that fully grasp critical issues in their business and deliver a customer value proposition that’s simple yet powerfully captivating. Suppliers can provide such a customer value proposition by making their offerings superior on the few elements that matter most to target customers, demonstrating and documenting the value of this superior performance, and communicating it in a way that conveys a sophisticated understanding of the customer’s business priorities.

This type of proposition differs from favorable points of difference in two significant respects. First, more is not better. Although a supplier’s offering may possess several favorable points of difference, the resonating focus proposition steadfastly concentrates on the one or two points of difference that deliver, and whose improvement will continue to deliver, the greatest value to target customers. To better leverage limited resources, a supplier might even cede to the next best alternative the favorable points of difference that customers value least, so that the supplier can concentrate its resources on improving the one or two points of difference customers value most. Second, the resonating focus proposition may contain a point of parity. This occurs either when the point of parity is required for target customers even to consider the supplier’s offering or when a supplier wants to counter customers’ mistaken perceptions that a particular value element is a point of difference in favor of a competitor’s offering. This latter case arises when customers believe that the competitor’s offering is superior but the supplier believes its offerings are comparable—customer value research provides empirical support for the supplier’s assertion.

To give practical meaning to resonating focus, consider the following example. Sonoco, a global packaging supplier headquartered in Hartsville, South Carolina, approached a large European customer, a maker of consumer packaged goods, about redesigning the packaging for one of its product lines. Sonoco believed that the customer would profit from updated packaging, and, by proposing the initiative itself, Sonoco reinforced its reputation as an innovator. Although the redesigned packaging provided six favorable points of difference relative to the next best alternative, Sonoco chose to emphasize one point of parity and two points of difference in what it called its distinctive value proposition (DVP). The value proposition was that the redesigned packaging would deliver significantly greater manufacturing efficiency in the customer’s fill lines, through higher-speed closing, and provide a distinctive look that consumers would find more appealing—all for the same price as the present packaging.

Sonoco chose to include a point of parity in its value proposition because, in this case, the customer would not even consider a packaging redesign if the price went up. The first point of difference in the value proposition (increased efficiency) delivered cost savings to the customer, allowing it to move from a seven-day, three-shift production schedule during peak times to a five-day, two-shift operation. The second point of difference delivered an advantage at the consumer level, helping the customer to grow its revenues and profits incrementally. In persuading the customer to change to the redesigned packaging, Sonoco did not neglect to mention the other favorable points of difference. Rather, it chose to place much greater emphasis on the two points of difference and the one point of parity that mattered most to the customer, thereby delivering a value proposition with resonating focus.

Substantiate Customer Value Propositions

In a series of business roundtable discussions we conducted in Europe and the United States, customer managers reported that “We can save you money!” has become almost a generic value proposition from prospective suppliers. But, as one participant in Rotterdam wryly observed, most of the suppliers were telling “fairy tales.” After he heard a pitch from a prospective supplier, he would follow up with a series of questions to determine whether the supplier had the people, processes, tools, and experience to actually save his firm money. As often as not, they could not really back up the claims. Simply put, to make customer value propositions persuasive, suppliers must be able to demonstrate and document them.

Value word equations enable a supplier to show points of difference and points of contention relative to the next best alternative, so that customer managers can easily grasp them and find them persuasive. A value word equation expresses in words and simple mathematical operators (for example, + and divide) how to assess the differences in functionality or performance between a supplier’s offering and the next best alternative and how to convert those differences into dollars.

Best-practice firms like Intergraph and, in Milwaukee, Rockwell Automation use value word equations to make it clear to customers how their offerings will lower costs or add value relative to the next best alternatives. The data needed to provide the value estimates are most often collected from the customer’s business operations by supplier and customer managers working together, but, at times, data may come from outside sources, such as industry association studies. Consider a value word equation that Rockwell Automation used to calculate the cost savings from reduced power usage that a customer would gain by using a Rockwell Automation motor solution instead of a competitor’s comparable offering:

Power Reduction Cost Savings = [kW spent x number of operating hours per year x $ per kW hour x number of years system solution in operation] Competitor Solution - [kW spent x number of operating hours per year x $ per kW hour x number of years system solution in operation] Rockwell Automation Solution

This value word equation uses industry-specific terminology that suppliers and customers in business markets rely on to communicate precisely and efficiently about functionality and performance.

Demonstrate Customer Value in Advance

Prospective customers must see convincingly the cost savings or added value they can expect from using the supplier’s offering instead of the next best alternative. Best-practice suppliers, such as Rockwell Automation and precision-engineering and manufacturing firm Nijdra Groep in the Netherlands, use value case histories to demonstrate this. Value case histories document the cost savings or added value that reference customers have actually received from their use of the supplier’s market offering. Another way that best-practice firms, such as Pennsylvania-based GE Infrastructure Water & Process Technologies (GEIW&PT) and SKF USA, show the value of their offerings to prospective customers in advance is through value calculators. These customer value assessment tools typically are spreadsheet software applications that salespeople or value specialists use on laptops as part of a consultative selling approach to demonstrate the value that customers likely would receive from the suppliers’ offerings.

When necessary, best-practice suppliers go to extraordinary lengths to demonstrate the value of their offerings relative to the next best alternatives. The polymer chemicals unit of Akzo Nobel in Chicago recently conducted an on-site two-week pilot on a production reactor at a prospective customer’s facility to gather data firsthand on the performance of its high-purity metal organics offering relative to the next best alternative in producing compound semiconductor wafers. Akzo Nobel paid this prospective customer for these two weeks, in which each day was a trial because of daily considerations such as output and maintenance. Akzo Nobel now has data from an actual production machine to substantiate assertions about its product and anticipated cost savings, and evidence that the compound semiconductor wafers produced are as good as or better than those the customer currently grows using the next best alternative. To let its prospective clients’ customers verify this for themselves, Akzo Nobel brought them sample wafers it had produced for testing. Akzo Nobel combines this point of parity with two points of difference: significantly lower energy costs for conversion and significantly lower maintenance costs.

Document Customer Value

Demonstrating superior value is necessary, but this is no longer enough for a firm to be considered a best-practice company. Suppliers also must document the cost savings and incremental profits (from additional revenue generated) their offerings deliver to the companies that have purchased them. Thus, suppliers work with their customers to define how cost savings or incremental profits will be tracked and then, after a suitable period of time, work with customer managers to document the results. They use value documenters to further refine their customer value models, create value case histories, enable customer managers to get credit for the cost savings and incremental profits produced, and (because customer managers know that the supplier is willing to return later to document the value received) enhance the credibility of the offering’s value.

A pioneer in substantiating value propositions over the past decade, GEIW&PT documents the results provided to customers through its value generation planning (VGP) process and tools, which enable its field personnel to understand customers’ businesses and to plan, execute, and document projects that have the highest value impact for its customers. An online tracking tool allows GEIW&PT and customer managers to easily monitor the execution and documented results of each project the company undertakes. Since it began using VGP in 1992, GEIW&PT has documented more than 1,000 case histories, accounting for $1.3 billion in customer cost savings, 24 billion gallons of water conserved, 5.5 million tons of waste eliminated, and 4.8 million tons of air emissions removed.

As suppliers gain experience documenting the value provided to customers, they become knowledgeable about how their offerings deliver superior value to customers and even how the value delivered varies across kinds of customers. Because of this extensive and detailed knowledge, they become confident in predicting the cost savings and added value that prospective customers likely will receive. Some best-practice suppliers are even willing to guarantee a certain amount of savings before a customer signs on.

A global automotive engine manufacturer turned to Quaker Chemical, a Pennsylvania-based specialty chemical and management services firm, for help in significantly reducing its operating costs. Quaker’s team of chemical, mechanical, and environmental engineers, which has been meticulously documenting cost savings to customers for years, identified potential savings for this customer through process and productivity improvements. Then Quaker implemented its proposed solution—with a guarantee that savings would be five times more than what the engine manufacturer spent annually just to purchase coolant. In real numbers, that meant savings of $1.4 million a year. What customer wouldn’t find such a guarantee persuasive?

Superior Business Performance

We contend that customer value propositions, properly constructed and delivered, make a significant contribution to business strategy and performance. GE Infrastructure Water & Process Technologies’ recent development of a new service offering to refinery customers illustrates how general manager John Panichella allocates limited resources to initiatives that will generate the greatest incremental value for his company and its customers. For example, a few years ago, a field rep had a creative idea for a new product, based on his comprehensive understanding of refinery processes and how refineries make money. The field rep submitted a new product introduction (NPI) request to the hydrocarbon industry marketing manager for further study. Field reps or anyone else in the organization can submit NPI requests whenever they have an inventive idea for a customer solution that they believe would have a large value impact but that GEIW&PT presently does not offer. Industry marketing managers, who have extensive industry expertise, then perform scoping studies to understand the potential of the proposed products to deliver significant value to segment customers. They create business cases for the proposed product, which are “racked and stacked” for review. The senior management team of GEIW&PT sort through a large number of potential initiatives competing for limited resources. The team approved Panichella’s initiative, which led to the development of a new offering that provided refinery customers with documented cost savings amounting to five to ten times the price they paid for the offering, thus realizing a compelling value proposition.

Sonoco, at the corporate level, has made customer value propositions fundamental to its business strategy. Since 2003, its CEO, Harris DeLoach, Jr., and the executive committee have set an ambitious growth goal for the firm: sustainable, double-digit, profitable growth every year. They believe that distinctive value propositions are crucial to support the growth initiative. At Sonoco, each value proposition must be:

- Distinctive. It must be superior to those of Sonoco’s competition.

- Measurable. All value propositions should be based on tangible points of difference that can be quantified in monetary terms.

- Sustainable. Sonoco must be able to execute this value proposition for a significant period of time.

Unit managers know how critical DVPs are to business unit performance because they are one of the ten key metrics on the managers’ performance scorecard. In senior management reviews, each unit manager presents proposed value propositions for each target market segment or key customer, or both. The managers then receive summary feedback on the value proposition metric (as well as on each of the nine other performance metrics) in terms of whether their proposals can lead to profitable growth.

In addition, Sonoco senior management tracks the relationship between business unit value propositions and business unit performance—and, year after year, has concluded that the emphasis on DVPs has made a significant contribution toward sustainable, double-digit, profitable growth.

Best-practice suppliers recognize that constructing and substantiating resonating focus value propositions is not a onetime undertaking, so they make sure their people know how to identify what the next value propositions ought to be. Quaker Chemical, for example, conducts a value-proposition training program each year for its chemical program managers, who work on-site with customers and have responsibility for formulating and executing customer value propositions. These managers first review case studies from a variety of industries Quaker serves, where their peers have executed savings projects and quantified the monetary savings produced. Competing in teams, the managers then participate in a simulation where they interview “customer managers” to gather information needed to devise a proposal for a customer value proposition. The team that is judged to have the best proposal earns “bragging rights,” which are highly valued in Quaker’s competitive culture. The training program, Quaker believes, helps sharpen the skills of chemical program managers to identify savings projects when they return to the customers they are serving.

As the final part of the training program, Quaker stages an annual real-world contest where the chemical program managers have 90 days to submit a proposal for a savings project that they plan to present to their customers. The director of chemical management judges these proposals and provides feedback. If he deems a proposed project to be viable, he awards the manager with a gift certificate. Implementing these projects goes toward fulfilling Quaker’s guaranteed annual savings commitments of, on average, $5 million to $6 million a year per customer.

Each of these businesses has made customer value propositions a fundamental part of its business strategy. Drawing on best practices, we have presented an approach to customer value propositions that businesses can implement to communicate, with resonating focus, the superior value their offerings provide to target market segments and customers. Customer value propositions can be a guiding beacon as well as the cornerstone for superior business performance. Thus, it is the responsibility of senior management and general management, not just marketing management, to ensure that their customer value propositions are just that.

출처: http://hbr.org/2006/03/customer-value-propositions-in-business-markets/ar/6